1. China constructing bridge on Pangong lake in Ladakh

It will bring down time to move troops and equipment

China is constructing a bridge in eastern Ladakh connecting the north and south banks of Pangong Tso (lake), which will significantly bring down the time for the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to move troops and equipment between the two sectors, two official sources independently confirmed on Monday.

“On the north bank, there is a PLA garrison at Kurnak fort and on the south bank at Moldo, and the distance between the two is around 200 km. The new bridge between the closest points on two banks, which is around 500 m, will bring down the movement time between the two sectors from around 12 hours to three or four hours,” one of the sources said. The bridge is located around 25 km ahead of the Line of Actual Control (LAC), the source stated.

The construction had been going on for some time and it would reduce the overall distance by 140-150 km, the other source said.

Earlier, the PLA had to take a roundabout crossing the Rudok county. But now the bridge would provide a direct axis, the first source said, adding that the biggest advantage with the new bridge was the inter-sector movement as the time would come down significantly. “They need to build piers for the bridge, which has been under way,” the source stated.

The bridge is in China’s territory and the Indian Army would have to now factor this in its operational plans, the source noted.

India holds one-third of the 135-km-long boomerang-shaped lake located at an altitude of over 14,000 feet. The lake, a glacial melt, has mountain spurs of the Chang Chenmo range jutting down, referred to as fingers.

The north bank, which has much higher differences in perception of the LAC than the south bank, was the initial site of the clashes in early May 2020, while tensions on the south bank flared up later in August.

The Indian Army got tactical advantage over the PLA on the south bank in August-end by occupying several peaks lying vacant since 1962, gaining a dominating view of the Moldo area. On the north bank too, the Indian troops set up posts facing PLA positions on the ridge-lines of Finger 4.

Background:

- Line of Actual Control is the disputed boundary between India and China. LAC is divided into three sectors: western, middle, and eastern.

- Both countries disagree on the actual location of the LAC. India claims that the LAC is 3,488 km long. But the Chinese believe it is around 2,000 km only.

- LAC mostly passes on the land, but in Pangong Tso lake, LAC passes through the water as well.

- The contested area of the lake is divided into 8 Fingers.

- Chinese contested that the LAC is at finger 4. But, India’s perceived LAC (Line of Actual Control) is at finger 8. This led to frequent disputes in the area.

- Previously India patrolled on foot up to Finger 8. But there is no motorable road access from India’s side to the areas east of Finger 4.

- China on the other hand already built a road on their side and dominated up to Finger 4.

- The recent (in May 2020) standoff on North and South bank of the lake is one such dispute.

- During the stand-off, Chinese troops marched to the ridgeline of finger 3 and 4. Indian forces were forced to stay within finger 3.

- But, in August 2020, India obtained some strategic advantages in the region by occupying certain peaks in the Kailash ranges. After that, Indian troops started positioning in Magar Hill, Mukhpari, Gurung Hill, etc. This pressurized China to enter into a negotiation.

- Later, India and China finally reached to an agreement on disengagement at Pangong Lake.

- The agreement was reached in the 9th corps commander meeting held on 24th January 2021.

What are the important points of agreement?

- The agreement calls for disengagement along the Pangong Tso region. It includes the pulling of tanks and troops from both sides.

- The troops will return to pre standoff position in a gradual manner on the north and south banks of the lake.

- In the north bank, China will pull back to finger 8 and India will get back to its Dhan Singh Thapa post near finger 3.

- The area between finger 3 and 8 will become a no patrolling zone for a temporary period.

- All the construction done after April 2020 will be removed by both sides

- Negotiation of the agreement through military and diplomatic discussions will take place to decide the patrolling on the area between finger 3 and 8.

What are the reasons leading to the present agreement?

First, India’s strategic advantage and ability to remain strong. China started the standoff in March and soon captured Finger 4 area. Chinese thought that they were in an advantageous position both militarily and strategically as compared to India (As the move coincides with COVID pandemic). China never expected such prolonged opposition from India. But India achieved this, which resulted into the agreement.

Second, there is also a climatic reason for it. The icy-cold winter in Ladakh with temperature as low as minus 20 degrees Celsius forced China for an agreement. Chinese forces are not habituated to such extreme temperature. For example, 10,000 troops from the Western Theatre Command (WTC) had moved to lower locations due to fatigue and other complications in January.

Third, sensible diplomacy of India. India handled the pressure from China very well. For example, handling the Chinese provoking tactics, India did not turn out aggressive at any point of dispute. All these along with India’s diplomatic will to ban Chinese apps forced China to engage in talks.

Fourth, International Pressure on China. China’s image in the international arena got deteriorated due to various reasons like

- China’s opaque way of handling COVID outbreak

- The way China forces its maritime neighbours in the South China Sea.

All these forces along with the standoff deteriorated China’s image. With the nations recovering from COVID pandemic, China wanted to create a positive image (as Chinese manufactured goods need markets). So China agreed to disengagement.

Fifth, New Biden-Harris alliance in the US promised greater stability in the South China Sea region. China cannot afford a conflict on its two fronts (East – South China Sea dispute, West – India – China standoff). So China agreed to return to pre-stand off position.

Concerns with the disengagement agreement:

First, there is a lack of trust amongst the countries. This restricts them from the attainment of lasting peace in the region.

Second, Ambiguity with respect to China’s intent. Even the US warned India to remain vigilant in disengagement.

Third, there is still a higher probability of escalation of violence in the region. For example, clashes in Galwan Valley started when the troops were pulling back in June last year.

Fourth, Pangong Tso is just one point of friction. Focus on other areas is also required. Else the efficacy of this disengagement is also at risk. The other areas include,

-

- Gogra Post at Patrolling Point 17A (PP17A)

- Hot Springs area near PP15

- PP14 in Galwan Valley

- Depsang Plains, which is close to India’s strategic Daulat Beg Oldie base

According to the present agreement, the discussion on Gogra Post and Hot Springs area will take place 48 hours after the disengagement at Pangong Tso Lake will complete.

Fifth, there is also an accusation on India for getting into agreement despite being in a dominant position. They are,

- Prior to the standoff, Finger 4 belonged to Indian territory. But in the agreement, India agreed to move to Finger 3 and not to stay on Finger 4.

- Indian troops, after capturing Kailash ranges are now moving back.

But one has to realize following points,

- China moving back to Finger 8 after capturing Finger 4.

- Focus on long term solution instead of the short term needs.

- Falling behind itself is like a defeat to China considering its military potential.

- The area between finger 3 to finger 8 is currently under negotiation.

2. ‘ISRO gearing up for multiple space missions in 2022’

K. Sivan says three new missions are in the pipeline

After a rather muted 2021 in terms of satellite launches, Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) is gearing up for a number of missions in 2022 including the launch of the first unmanned mission of Gaganyaan, its Chairman, K. Sivan said.

In his New Year’s message for 2022, Mr. Sivan said ISRO had a number of missions to execute this year. These include the launch of the Earth Observation Satellites, EOS-4 and EOS-6 on board the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV), and the EOS-02 on board the maiden flight of the Small Satellite Launch Vehicle (SSLV). “[ISRO has] many test flights for Crew Escape System of Gaganyaan and launch of the first unmanned mission of Gaganyaan. In addition, we also have Chandrayaan-03, Aditya Ll, XpoSat, IRNSS and technology demonstration missions with indigenously developed advanced technologies,” he said. Design changes on Chandrayaan-3 and testing has seen huge progress, he said.

Mr. Sivan said the hardware in loop test of Aditya L1 spacecraft and accommodation studies for XpoSat in the SSLV have been completed and ISRO has delivered the S-band SAR payload to NASA for NISAR [NASA-ISRO SAR] mission. The NISAR mission, scheduled for launch in 2023, is optimised for studying hazards and global environmental change and can help manage natural resources better and provide information to scientists to better understand the effects and pace of climate change.

Three new space science missions are also in the pipeline, Mr. Sivan said. These include a Venus mission, DISHA –a twin aeronomy satellite mission and TRISHNA, an ISRO-CNES [Centre national d’études spatiales] mission in 2024.

PSLV Vs GSLV

Both PSLV (Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle) and GSLV (Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle) are the satellite-launch vehicles (rockets) developed by ISRO. PSLV is designed mainly to deliver the “earth-observation” or “remote-sensing” satellites with lift-off mass of up to about 1750 Kg to Sun-Synchronous circular polar orbits of 600-900 Km altitude.

The remote sensing satellites orbit the earth from pole-to-pole (at about 98 deg orbital-plane inclination). An orbit is called sun-synchronous when the angle between the line joining the centre of the Earth and the satellite and the Sun is constant throughout the orbit.

Due to their sun-synchronism nature, these orbits are also referred to as “Low Earth Orbit (LEO)” which enables the on-board camera to take images of the earth under the same sun-illumination conditions during each of the repeated visits, the satellite makes over the same area on ground thus making the satellite useful for earth resources monitoring.

Apart from launching the remote sensing satellites to Sun-synchronous polar orbits, the PSLV is also used to launch the satellites of lower lift-off mass of up to about 1400 Kg to the elliptical Geosynchronous Transfer Orbit (GTO).

PSLV is a four-staged launch vehicle with first and third stage using solid rocket motors and second and fourth stages using liquid rocket engines. It also uses strap-on motors to augment the thrust provided by the first stage, and depending on the number of these strap-on boosters, the PSLV is classified into its various versions like core-alone version (PSLV-CA), PSLV-G or PSLV-XL variants.

The GSLV is designed mainly to deliver the communication-satellites to the highly elliptical (typically 250 x 36000 Km) Geosynchronous Transfer Orbit (GTO). The satellite in GTO is further raised to its final destination, viz., Geo-synchronous Earth orbit (GEO) of about 36000 Km altitude (and zero deg inclination on equatorial plane) by firing its in-built on-board engines.

Due to their geo-synchronous nature, the satellites in these orbits appear to remain permanently fixed in the same position in the sky, as viewed from a particular location on Earth, thus avoiding the need of a tracking ground antenna and hence are useful for the communication applications.

Two versions of the GSLV are being developed by ISRO. The first version, GSLV Mk-II, has the capability to launch satellites of lift-off mass of up to 2,500 kg to the GTO and satellites of up to 5,000 kg lift-off mass to the LEO. GSLV MK-II is a three-staged vehicle with first stage using solid rocket motor, second stage using Liquid fuel and the third stage, called Cryogenic Upper Stage, using cryogenic engine.

3. The deafening silence of scientists

Few Indian scientists argue for the freedom of thought and are able to stand up against pseudoscience

In December 1954, Meghnad Saha, one of India’s foremost astrophysicists and an elected parliamentarian, wrote to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, “My request to you is that you do not smother your Desdemonas on the report of men like this particular Iago. I sometimes believe there are too many Iagos about you, as there have been in history about every person of power and prestige”. By referring to the characters in Shakespeare’s Othello, an aggrieved Saha was showing his displeasure at a situation that he perceived to be bad for Indian science wherein the courtship between the state and science was being ruined by the Machiavellian advisers of the then Prime Minister.

A glorious tradition forgotten

We have come a long way from Nehruvian times when scientists could afford to be directly critical of the Prime Minister and still expect to get a pat on their shoulder in return. Over the past few years, a pernicious political landscape that encourages intolerance and superstition has been developed. This has proved to be non-conducive for the time-tested scientific model and freedom of inquiry. For the creation of knowledge, one should be able to think and express themselves freely. One also needs to have a space for dissent, which is a fundamental requirement for democracies to thrive. Are our scientists vocal enough to argue for the freedom of thought and are they able to stand up against pseudoscience? Their silence has given rise to the perception that they too are complicit in creating an unhealthy atmosphere of ultra-nationalism and jingoism, where the glorious tradition followed by socially committed scientists like Saha is forgotten.

We have seen this lack of reactivity from Indian scientists and science academies on many occasions in the recent past, starting with the conduct of the 102nd Indian Science Congress in 2015. How did a session suffused with extreme nationalism and promoting junk science find its way into this prestigious meet? How was it vetted and approved by a high-profile committee containing the country’s front-ranking scientists? Completely sidelining the real scientific contributions made in ancient and medieval times, ridiculous claims were made in that forum about ancient ‘Bharat’ being a repository of all modern knowledge. Except a few, like the late Pushpa Bhargava, who always fretted about the lack of scientific temper among Indian scientists, most of our leaders in science chose to ignore something that was patently wrong.

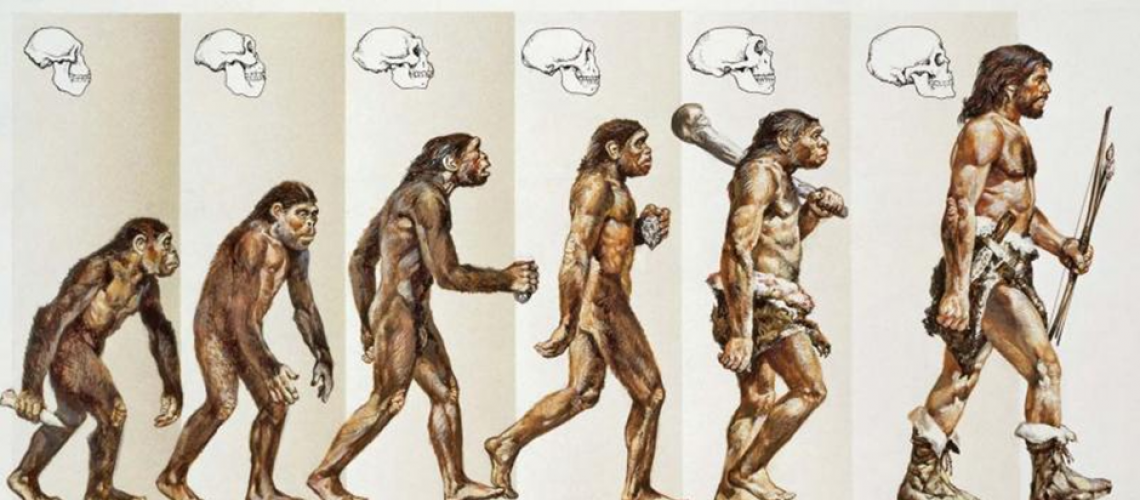

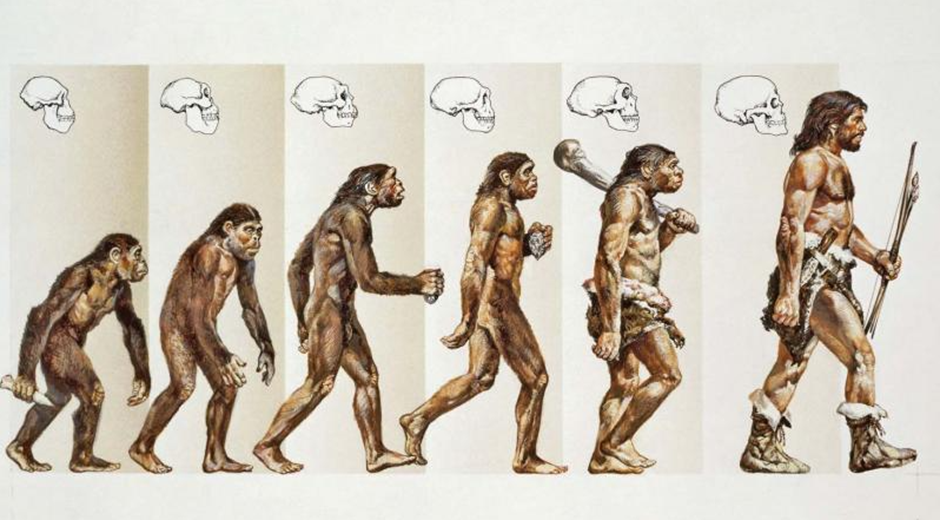

Pseudo-scientific remarks by responsible political leaders have continued to hog the limelight ever since. Even when a former Union Minister insisted that Darwin’s Theory of Evolution was scientifically wrong, leading scientists remained silent save a few. More recently, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh chief made a misinformed statement that the DNA of all the people in India has been the same for 40,000 years. His message clearly goes against the proven fact that Indians have mixed genetic lineages originating from Africa, the Mediterranean, and Eurasian steppes. As a part of revisionist history-writing, the Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur has now issued a 2022 calendar. The purpose of it is to argue for a Vedic cultural foundation for the Indus Valley Civilisation — a theory that goes against all the available evidence; morphing an Indus Valley single-horned bull seal into a horse will not solve the evidentiary lacuna. A retinue of junk science propagators and new-age ‘gurus’ have been flourishing in this anti-science environment, often marketing questionable concoctions including cow products to cure COVID-19 and even homosexuality, as though it is some sort of disease. Pseudoscience has provided a foundational base for a huge money-making industry that successfully peddles quackery by sustaining and exploiting the people’s ignorance.

Our social and political life resonates uncannily with the fascist era of the 1930s-40s when Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini argued that the “white race” was locked in a deadly demographic competition with races of “lesser purity” whose numbers were growing much faster. It can be instructive in our current political climate to reflect on how science failed as a bulwark against such regressive viewpoints. The science historian, Massimo Mazzotti, at the University of California, Berkeley, ably showed how the fascist regime in Italy, using various intimidation and surveillance tactics, made academic elites toe the official line. The faculties did so without making an actual anti-fascist choice. Instead, they entered the grey zone of cynical detachment. It was due to cynicism and careerism that the scientists of Italy derided racist policies as foolish in private but did not bother to question them publicly. Like Italy, racism and ‘othering’ was very much a part of the political landscape in Germany under the Nazi regime, which saw a big exodus of high-ranking scientists with Jewish tags.

Reasons for toeing the line

As discussed by Naresh Dadhich, an Indian theoretical physicist, in an article, one of the reasons for this acquiescence is that scientific research relies almost entirely on funding from the government. So, a fear of retribution acts against the idea of engagement with society. Another equally valid reason is that our contemporary science researchers remain entirely cut off from liberal intellectual discourse, unlike in the initial years after Independence. For most scientists today, the idea of science as a form of argument remains foreign. For many of them, exposure to the social sciences is minimal at university. They also don’t get trained in a broad range of social topics at the school level.

Globally, STEM students downplay altruism and arguably demonstrate less social concern than students from other streams. The blame squarely lies with the pedagogy followed in our science education system. The leading science and technology institutes recruit students right after school and largely host one or two perfunctory social science courses. Students, thus, mostly remain oblivious to the general liberal intellectual discourse. This issue is of major concern, as the 21st century is witnessing a new rise of illiberal democracy with fascist tendencies that generate intolerance and exclusion in various parts of the world, including India. We are also living at a time when scientific advice is marginalised in public policy debates ranging from natural resource use to environmental impacts.

In the early 20th century, many leading scientists were deeply engaged with philosophy and had developed a distinctive way of thinking about the implications of science on society. They were much more proactive about societal issues. The continuity of that legacy appears to have broken. A cowed-down scientific enterprise is not helpful in retaining the secular autonomy of academic pursuits. To regain this cultural space among younger practitioners, science education must include pedagogical inputs that help learners take a deliberative stand against false theories that could undermine civil society and democratic structures.

4. RBI approves small, offline e-payments

It aims to promote usage in rural areas

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has come out with the framework for facilitating small-value digital payments in offline mode, a move that would promote digital payments in semi-urban and rural areas.

The framework incorporates feedback received from the pilot experiments on offline transactions conducted in different parts of the country between September 2020 and June 2021.

An offline digital payment does not require Internet or telecom connectivity.

“Under this new framework, such payments can be carried out face-to-face (proximity mode) using any channel or instrument like cards, wallets and mobile devices,” the RBI said.

“Such transactions would not require an Additional Factor of Authentication. Since the transactions are offline, alerts (by way of SMS and / or e-mail) will be received by the customer after a time lag,” it added.

There is a limit of ₹200 per transaction and an overall limit of ₹2,000 until the balance in the account is replenished. The RBI said the framework took effect ‘immediately’.

5. Extending the GST compensation

What is the GST payment due to States? Why are several States demanding a continuation of the compensation beyond June 2022?

Ahead of the 46th meeting of the GST Council, Finance Ministers of several States at a pre-Budget interaction with the Union Finance Minister demanded that the GST compensation scheme be extended beyond June 2022.

The adoption of GST was made possible by States ceding almost all their powers to impose local-level indirect taxes and agreeing to let the prevailing multiplicity of imposts be subsumed into the GST. This was agreed on the condition that revenue shortfalls arising from the transition to the new indirect taxes regime would be made good from a pooled GST Compensation Fund for a period of five years that is set to end in June 2022.

With the finances of most States having been severely hit in the wake of the pandemic, States have been hard pressed to find ways to garner the resources to meet the essential and additional spending necessitated by the public health crisis.

The story so far: Just a day ahead of the 46th meeting of the GST Council on December 31, the Finance Ministers of several States had a pre-Budget interaction with the Union Finance Minister and demanded that the GST compensation scheme be extended beyond June 2022, when it is set to expire. Citing the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the overall economy and more specifically States’ revenues, the States including Tamil Nadu, Kerala, West Bengal, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh stressed that while their revenues had been adversely impacted by the introduction of GST, the hit from the pandemic had pushed back any possible rebound in revenue especially at a time when they had been forced to spend substantially more to address the public health emergency and its socio-economic fallout on their residents.

What is the GST compensation?

The Constitution (One Hundred and First Amendment) Act, 2016, was the law which created the mechanism for levying a common nationwide Goods and Services Tax (GST). The adoption of GST was made possible by States ceding almost all their powers to impose local-level indirect taxes and agreeing to let the prevailing multiplicity of imposts be subsumed into the GST. While States would receive the SGST (State GST) component of the GST, and a share of the IGST (integrated GST), it was agreed that revenue shortfalls arising from the transition to the new indirect taxes regime would be made good from a pooled GST Compensation Fund for a period of five years that is currently set to end in June 2022. This corpus in turn is funded through a compensation cess that is levied on so-called ‘demerit’ goods. The computation of the shortfall is done annually by projecting a revenue assumption based on 14% compounded growth from the base year’s (2015-2016) revenue and calculating the difference between that figure and the actual GST collections in that year.

What is the shortfall for the current fiscal year ending on March 31?

On October 28, the Union government said the Ministry of Finance had released ₹44,000 crore to the States and Union Territories “under the back-to-back loan facility in lieu of GST Compensation”. After taking into account earlier releases amounting to ₹1,15,000 crore, the total amount released in the current financial year as back-to-back loan in-lieu of GST compensation was ₹1,59,000 crore, it added at the time. The Centre clarified that this sum was in addition to normal GST compensation “being released every 2 months out of actual cess collections” that is estimated to exceed ₹1 lakh crore. “The sum total of ₹2.59 lakh crore is expected to exceed the amount of GST compensation accruing in FY 2021-22,” the Union Ministry of Finance said at the time.

It also explained that the decision for the Union government to borrow the ₹1.59 lakh crore and release it to the States and UTs, which had been taken in the 43rd GST Council Meeting held on May 25, 2021, was aimed at bridging the resource gap due to the short release of compensation on account of the amount accruing into the Compensation Fund being inadequate.

Why are several States seeking an extension of the GST compensation sunset timeline?

With the finances of most States having been severely hit in the wake of the pandemic and the economic slowdown that had preceded the outbreak of COVID-19 in early 2020, the State governments have been hard pressed to find ways to garner the resources to meet the essential and additional spending necessitated by the public health crisis.

Tamil Nadu’s Finance Minister Palanivel Thiaga Rajan had last week stressed that with the States’ revenues yet to recover, and considering the huge revenue shortfall that was anticipated, it was necessary that the period of GST compensation be extended by at least two years beyond June 2022. He emphasised that at the time of introduction of GST, the States had agreed to forego their fiscal autonomy with an assurance from the Union government that their revenues would be protected. However, over the last five years, there had been a widening gap between the actual revenues realised and the protected revenues guaranteed. While the trend had been visible even before the pandemic, the gap had widened ever since, Mr. Rajan had observed. This view was broadly echoed by other States including Kerala, Rajasthan and Delhi, with most of them seeking an extension for five years.

Can the deadline be extended? If so, how?

The deadline for GST compensation was set in the original legislation and so in order to extend it, the GST Council must first recommend it and the Union government must then move an amendment to the GST law allowing for a new date beyond the June 2022 deadline at which the GST compensation scheme will come to a close.

Interestingly, even now the compensation cess will continue to be levied well beyond the current fiscal year since the borrowings made in lieu of the shortfalls in the compensation fund would need to be met. In September, the GST Council decided to extend the compensation cess period till March 2026 “purely to repay the back-to-back loans taken between 2020-21 and 2021-22”.

6. What Russia hopes to do by ratcheting up tensions with Ukraine

Why is Russia continuing its military build-up along the border it shares with Ukraine? How is the West responding?

Russia has amassed more than 1,00,000 troops at its border with aspiring NATO member Ukraine. Russia stated that only if NATO withdraws their forces from all countries in Europe that joined the alliance after May 1997, would they de-escalate the military build-up.

The U.S and NATO officials have bluntly stated that Russia’s proposals are unrealistic. They insist that Ukraine and every other country has the right to determine its own foreign policy.

Germany has also warned Russia that the Nord Stream pipeline would be stopped if they were to invade Ukraine.

The story so far: Tensions between Russia and the West have been rising for months now. Russia has amassed more than 1,00,000 troops at its border with aspiring NATO member Ukraine, prompting fears that it is planning to invade its neighbour. While Russia has denied such plans, it has, at the same time, stated that the troop deployment is in response to NATO’s refusal to cap its steady expansion eastward. Putting the onus of de-escalation on the West, Kremlin has put forward a series of proposals outlining the conditions that must be met before it would scale back its mobilisations. But the U.S. and NATO, while agreeing to talks, have said Moscow’s proposals cannot be taken seriously. U.S. President Joe Biden has also assured his Ukrainian counterpart Volodymyr Zelensky that the U.S. will “respond decisively” in case of an invasion by Russia.

What are Russia’s demands?

At a press conference in December, Russia’s President Vladimir Putin, when asked if he could guarantee that Russia won’t invade Ukraine, replied that it would depend on “unconditional compliance with Russian security demands”. Russia released these demands in the form of draft security pacts in December. Foremost among them is that NATO should withdraw troops and weapons from all countries in Europe that joined the alliance after May 1997, in the aftermath of the collapse of the Soviet Union. This would effectively mean that NATO cannot operate in any of the Baltic nations that border Russia (Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania), central European states such as Poland, Hungary, and the Czech republic, and Balkan states such as Croatia and Slovenia. Russia also wants NATO to drop plans of any further ‘enlargement’, which means committing to not accepting Ukraine and Georgia as members. Another demand is that NATO must not hold drills in eastern Europe, Ukraine and Georgia without prior approval from Russia.

What has been the West’s response to Russia’s proposals?

American and NATO officials, while indicating that they are open to negotiations, have bluntly stated that Russia’s proposals are unrealistic. Citing the principle of sovereignty, they insist that Ukraine, and every other country in eastern Europe, has the right to determine its foreign policy without outside interference and join whichever alliance it wants. They have also dismissed the idea of Russia wielding veto power over who gets to become a member of NATO, and pointed out that NATO would not take decisions affecting eastern Europe without involving the countries concerned. In other words, they believe that Russia, by amassing troops at the Ukrainian border and ratcheting up tensions, is hoping to negotiate the regional security architecture directly with Washington, bypassing the small European states. But both the U.S. and NATO have indicated that they would not want to fall into this trap and will instead consult their European allies on their negotiations with Kremlin.

How do the rising tensions impact the Nord Stream 2 pipeline ?

The Nord Stream 2 pipeline is complete but has to get multiple clearances before gas starts flowing through it. As and when it gets operational, it would double the volume of gas supplied by Russia’s Gazprom to Europe’s industrial powerhouse Germany. With Greens a part of the ruling coalition, Germany is keen to phase out coal and nuclear energy. It desperately needs cheap gas, which is why former Chancellor Angela Merkel approved the Nord Stream 2. But Germany’s Vice Chancellor and Economic Affairs and Climate Action Minister Robert Habeck (from the Green Party) has termed the pipeline as “a mistake from a geopolitical perspective”, and has warned of “severe consequences”, including stopping the Nord Stream pipeline, if Russia were to invade Ukraine. American state department officials have also indicated that sanctions against Nord Stream 2 are a certainty in case of an invasion.

What next?

Senior officials from the U.S. and Russia, led by Deputy Secretary of State Wendy Sherman and Deputy Foreign Minister Sergei Ryabkov, will hold talks in Geneva on January 10 to try and work out a path towards de-escalation. Negotiations are also expected to continue a couple of days later at the Organisation for Security and Co-operation (OSCE) in Vienna. While Russia is expected to continue its tactic of deploying brinkmanship in pursuit of geopolitical goals, the U.S. will seek to leverage the possibility that an actual invasion would only make the states in the region cling tighter to NATO, by making the Russian threat more real and urgent.

7. Weighing in on the efficacy of female leadership

It is necessary to get rid of inherent biases and perceptions about the effectiveness of women in roles of authority

A recent study in the U.S reports that States which have female governors had fewer COVID-19 related deaths. The authors of the study conclude that women leaders are more effective than their male counterparts in times of crises. While there is danger in making sweeping generalisations, the important takeaway from such studies is the necessity of getting rid of inherent biases about female effectiveness in leadership roles.

In India, women were allowed to vote from 1950 onwards and so could participate on an equal footing with men from the first general election of 1951-52. This is in contrast to the experience in the so-called “mature democracies” of western Europe and U.S.

The underrepresentation of women in Indian legislatures is striking. Even though the 2019 election sent the largest number of women to Lok Sabha, women constitute just over 14% of its total strength. Attempts have also been made to extend quotas for women in parliament through a Women’s Reservation Bill. But even after being tabled 24 years ago, it has not been passed by the lower houses.

The lack of representation of women in a parliamentary panel examining a bill to increase the legal age of marriage for women from 18 to 21 years has come under scrutiny following the comments of Rajya Sabha MP Priyanka Chaturvedi. In this piece dated September 24, 2020, Bhaskar Dutta explains how prejudices about the efficacy of women in key political roles need to be systemically eradicated.

What do Germany, Taiwan and New Zealand have in common? These are all countries that have women heading their governments. And although they are located in three different continents, the three countries seem to have managed the pandemic much better than their neighbours. Much along the same lines, a detailed recent study by researchers in the United States reports that States which have female governors had fewer COVID-19 related deaths, perhaps partly because female governors acted more decisively by issuing earlier stay-at-home orders. The authors of the study conclude that women leaders are more effective than their male counterparts in times of crises. There will be several critics (no need to guess their gender) who will question the reliability of this conclusion by pointing out deficiencies in the data — admittedly somewhat limited — or the econometric rigour of the analysis. Many will also point out that it is dangerous to make sweeping generalisations based on one study.

The point about the danger of making sweeping generalisations is valid. Of course, studies such as these do not establish the superiority of all female leaders over their male counterparts. All female leaders are not necessarily efficient, and there are many men who have proved to be most effective and charismatic leaders. The important takeaway from the recent experience and such studies is the necessity of getting rid of inherent biases and perceptions about female effectiveness in leadership roles.

India’s gram panchayats

Importantly, female leaders also bring something quite different to the table. In particular, they perform significantly better than men in implementing policies that promote the interests of women. This was demonstrated in another study conducted by Nobel Laureate Esther Duflo and co-author Raghabendra Chattopadhyay, who used the system of mandated reservations of pradhans in gram panchayats to test the effectiveness of female leadership. Their study was made possible by the 1993 amendment of the Indian Constitution, which mandated that all States had to reserve one-third of all positions of pradhan for women. Since villages chosen for the mandated reservations were randomly selected, subsequent differences in investment decisions made by gram panchayats could be attributed to the differences in gender of the pradhans. Chattopadhyay and Duflo concluded that pradhans invested more in rural infrastructure that served better the needs of their own gender. For instance, women pradhans were more likely to invest in providing easy access to drinking water since the collection of drinking water is primarily, if not solely, the responsibility of women.

In addition to the instrumental importance of promoting more space for women in public policy, this is also an important goal from the perspective of gender equality. The right to vote is arguably the most important dimension of participation in public life. There are others. What proportion of women stand for election to the various State and central legislatures? How many are elected? Perhaps more important, how many women occupy important positions in the executive branch of government?

About suffrage

Independent India can rightly be proud of its achievement in so far as women’s suffrage is concerned. Women were allowed to vote from 1950 onwards and so could participate on an equal footing with men from the first general election of 1951-52. This is in striking contrast to the experience in the so-called “mature democracies” of western Europe and the United States. In the U.S., it took several decades of struggle before women were allowed to vote in 1920. Most countries in Europe also achieved universal suffrage during the inter-war period. Since most able- bodied men went away to the battlefields during the First World War, increasing numbers of women had the opportunity to show that they were adequate substitutes in activities that were earlier the sole preserve of men. This, it is suggested, mitigated the anti-female bias and earned women the right to vote in European countries.

We have had and have charismatic female leaders like Indira Gandhi, Jayalalitha, Mayawati, Sushma Swaraj and Mamata Banerjee among several others. Interestingly, a glaring example of gender stereotyping was the labelling of Indira Gandhi as the “only man in the cabinet”. Apart from these stalwarts, the overall figures are depressing. The female representation in the current National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government at the Centre is probably not very far from the typical gender composition in Indian central and State governments. Female members make up only about 10% of the total ministerial strength. The underrepresentation of female Ministers in India is also reflected in the fact that Ms. Banerjee is currently the only female Chief Minister.

The underrepresentation of women in Indian legislatures is even more striking. For instance, the 2019 election sent the largest number of women to the Lok Sabha. Despite this, women constitute just over 14% of the total strength of the Lok Sabha. This gives us the dismal rank of 143 out of 192 countries for which data are reported by the Inter-Parliamentary Union. Tiny Rwanda comes out on top with a staggering 60% of seats in its lower house occupied by women.

Since women running for elections face numerous challenges, it is essential to create a level-playing field through appropriate legal measures. The establishment of quotas for women is an obvious answer. I have mentioned earlier that mandated reservation for women in gram panchayats was established in all major States since the mid-1990s. Attempts have also been made to extend quotas for women in the Lok Sabha and State Assemblies through a Women’s Reservation Bill. Unfortunately, the fate of this Bill represents a blot on the functioning of the Indian Parliament. The Bill was first presented to the Lok Sabha by the H.D. Deve Gowda government in 1996. Male members from several parties opposed the Bill on various pretexts. Subsequently, both the NDA and United Progressive Alliance governments have reintroduced the Bill in successive Parliaments, but without any success. Although the Rajya Sabha did pass the bill in 2010, the Lok Sabha and the State legislatures are yet to give their approval — despite the 24 years that have passed since it was first presented in the Lok Sabha.

Steps to reducing prejudice

Of course, there is a simple fix to the problem. The major party constituents of the NDA and UPA alliances can sidestep the logjam in Parliament by reserving say a third of party nominations for women. This will surely result in increasing numbers of women in legislatures and subsequently in cabinets. The importance of this cannot be overestimated. There is substantial evidence showing that increased female representation in policy making goes a long way in improving perceptions about female effectiveness in leadership roles. This decreases the bias among voters against women candidates, and results in a subsequent increase in the percentage of female politicians contesting and winning elections. So, such quotas have both a short-term and long-term impact. Indeed, voter perceptions about the efficacy of female leadership may change so drastically in the long run that quotas may no longer be necessary!